Not that there were exactly any spoilers to the story, but at this point if you were planning to watch the “new” Beatles documentary Get Back I figure you’ve probably seen it by now. There was quite a lot to take in, literally – nearly eight hours of running time over its three episodes – with many incredible segments, some truly chills-inducing moments, and more than a few surprises. And, if I’m being honest, at times it also felt like a bit of a slog. I mean, these were the legendary Beatles, the living, breathing characters themselves in vivid real-life like we’d scarcely, if ever, seen them before. So that in itself was absolutely thrilling. But there was also a fair amount of, well, practically nothing. Sitting around, waiting on arrivals, adjusting equipment, sound-checking, bullshitting, clowning, taking breaks, a small amount of activity and then more breaks, and the seemingly endless circular conversations about what they were planning to do, how they might be planning to do it, and the ways they were really going to make that happen…starting tomorrow (followed soon by the day after that). As the owner of a long-time band rehearsal site – our basement, for my son’s group – I’d seen these particular behaviors first-hand for many years. I just couldn’t really believe it: this is how John, Paul, George & Ringo acted too?!

And still, the biggest takeaway for me from the marathon of tapes – edited down to the eight hours shown from over 60 hours of film footage and 150 hours of audio originally recorded – wasn’t anything at all what I expected. Not Yoko parking herself in the quartet’s sanctum like a squatter; not George’s low-key walkabout from the band, and John’s casual suggestion that he be replaced by Eric Clapton; not how much tea and toast the boys consumed (even spreading their own marmalade), and by God, how they chain-smoked cigarettes. No, the most jarring thing for me was the realization – perhaps all too obvious in retrospect – that these songs, these classics of the Beatles’ catalog that we’ve heard hundreds and hundreds of times in the decades since the 1970 filming, did not have to be as we know them. That they need not have become what we take for granted as the way that they sound, played over and over on our stereos and in our minds. Though they seem stamped by history as the popular music standards that they are, their composition, their components, even their mere existence, was anything but assured. What was most striking, then, was their utter lack of inevitability.

Prolific music industry observer Bob Lefsetz extensively covered the Get Back series – as he does about basically all music, pop culture and even business and political scenarios – and nailed this straightforward yet conspicuous insight. “Records are finite,” he wrote. “But until they’re finished, they’re fluid.” How the songs evolved, literally, during their often stilted process, to come to be what we’ve known them as, what it seems like we’ve heard forever, was riveting: what words got changed, what parts were rearranged, what instrumentation was added, how the producer’s ideas meshed with the engineers, or with the songwriters. We even witnessed the history-altering serendipity of simply who dropped by the studio, Billy Preston, without whose integral contributions the record’s sound, its chemistry, even its ultimate completion, must be deemed as uncertain. “The noodling, the disagreements, the endless repetition, the tweaking,” observed Lefsetz. “The definitive statements are elusive.”

Nowhere was this passage more dramatic in the film, however, than during McCartney’s early-morning presentation of the title track ‘Get Back.’ In real time we (along with the yawning George and Ringo) were onlookers able to watch the progression from Paul strumming out some seemingly aimless chords on a guitar while half-singing/humming mostly unformed phrases, only to have the makings of a hit single emerge in a matter of minutes. Like he’d conjured it. John eventually shows up (late arriving per usual), throws on his guitar and begins playing along to the just-unfolding piece. As if it had been there all along. The transformation was mind-blowing stuff. “It was created on barely more than a whim, Lefsetz said, “and it’s forever!”

I’m not entirely sure why I was surprised that the creative process was, well, a process. That Michelangelo didn’t just arrive in Florence with the statue of David intact but had to chisel its existence into being, somehow connecting with his unique brilliance to make it so. But in a way, maybe that’s the point: this wasn’t just any band, these were The Beatles. And the works we witnessed being created, like David, were masterpieces. Charles Reynolds, a renowned scholar of magic, once famously said: “By reading enough books in enough libraries, you could learn how any trick is done. But that doesn’t mean you can do it.” And really, what is the enchanting music of The Beatles if not unexplained magic.

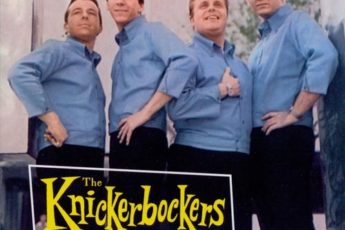

(the “finished” product)

By the way, for a time the conclusion to George’s line in ‘Something’ – “Something in the way she moves / attracts me like…” – was a choice between “cauliflower” and “pomegranate”

Rob MacMahon

February 25, 2022 2:21 pmIt is indeed crazy to watch these now classic songs emerge from such an embryonic stage.