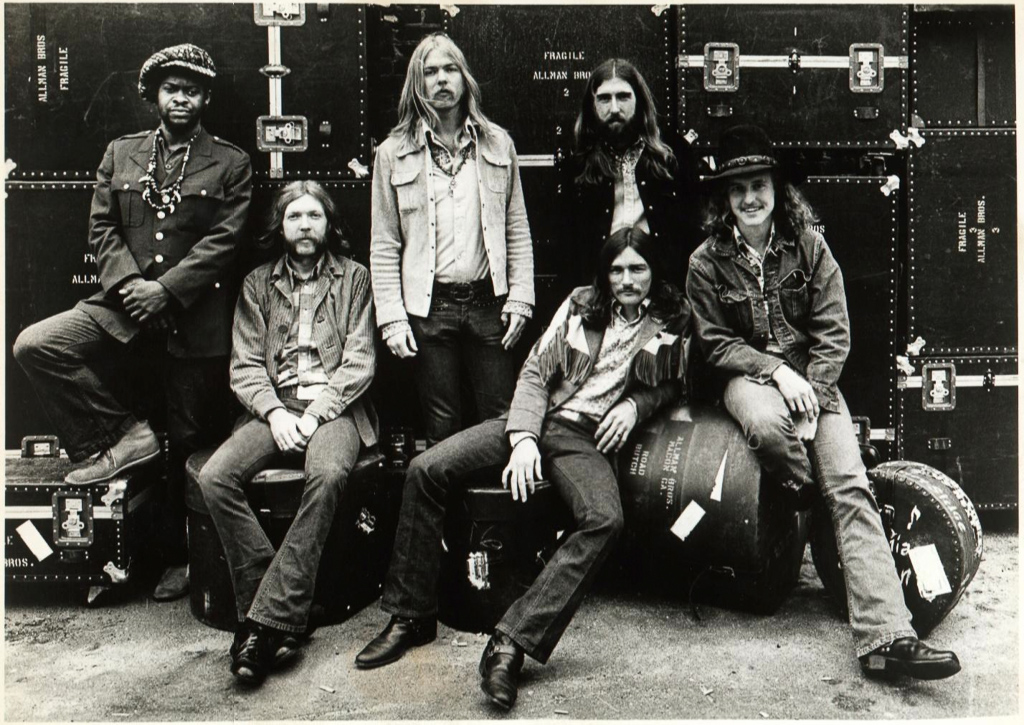

Is it possible the most influential member of a band that existed for 45 years was in it for just it’s first 3? Duane Allman was one of 6 founding members of the Allman Brothers Band in Jacksonville, Florida in 1969 – along with his brother Gregg Allman, Dickey Betts, Berry Oakley, Butch Trucks, and the man known as Jaimoe – but in those earliest formative years he was the band’s unquestioned leader, the big brother to Gregg yet figuratively to all. And then in 1971 he was already gone, the victim of a fatal motorcycle crash in Macon, Georgia at the age of 24. In that brief era, led by Duane, the band had already released three albums, with a fourth in the works, that may as well stand as the Mount Rushmore of American rock music: The Allman Brothers Band (1969), Idlewild South (1970), At Fillmore East (1971), and Eat A Peach (1972). Said Trucks, “We thought about quitting because how could we go on without Duane? But then we realized: How could we stop.” In the ensuing four decades, up until the band’s official end on the night of October 28th, 2014, the incredible musical foundation built by Duane over just those three years propelled them every note of the way.

Personally, I didn’t discover “The Brothers” until their next album, the first entirely post-Duane recording, 1973’s Brothers and Sisters, by which time bassist Oakley had also been killed following a motorcycle accident eerily similar to Duane’s, crashing just three blocks from where Duane had perished. Tunes like ‘Wasted Words,’ ‘Southbound,’ ‘Jessica,’ and the song that would become the Allmans first and only hit single, ‘Ramblin’ Man,’ catapulted the band to their commercial peak, and convinced me that they were the foremost progenitors of the southern rock movement. I remember hearing an FM radio DJ describe them at that time as a blues band and feeling confused and even offended; somehow their existing recordings of ‘It’s Not My Cross To Bear,’ ‘Dreams,’ ‘Hoochie Coochie Man,’ and for chrissakes, ‘Statesboro Blues’ and ‘Stormy Monday’ had not yet appeared on my radar to etch their unmistakable blues roots. The truth, of course, is that they were always both, southern rock and the blues, as well as able to incorporate healthy amounts of jazz and country, and by god some hellacious jamming (the infamous ‘Mountain Jam’ track covered almost 35-minutes and occupied two entire sides of the Eat A Peach album). Some other bands may have come close, but I don’t believe anyone has ever equaled the distinctive musical conglomeration – of styles, influences, razor-sharp execution, and those signature twin-guitar harmonies (coining “guitarmony”) – as that of the Allmans. By the way, the Allmans’ historical significance also extends beyond music: Many give them credit, including the candidate himself, for spearheading Jimmy Carter’s successful run for the presidency in 1976. “Gregg Allman and the Allman Brothers just about put me in the White House,” Carter said. “(They) were better known than I was at that time, and got the campaign political attention. They were the best fundraisers that we had.”

Then for a stretch the Behind The Music-like downward story arc took over: Gregg suffered some drug but mostly heavy drinking issues, power struggles with Dickey became epidemic, infighting and lineup changes plagued band chemistry, their production and musical direction became wayward, until after a while there just was no Allman Brothers Band. Not for about 7 years. “We broke up in ’82 because we decided we better just back out or we would ruin what was left of the band’s image,” said Betts. When the next generation of the Allman Brothers Band eventually grew again it did so, one might say, like a mushroom, out of the loam of a grimy old theater on the upper west side of Manhattan.

In 1989 the Allmans reunited and began their final act, playing 4 shows at New York’s Beacon Theater. By 1992 they had played 10 shows there, and following that they played as many as 19 shows at The Beacon each year during stretches that normally extended into three-week residencies, and became a “New York rite of spring” (long-time Rolling Stone music critic, David Fricke, said it was never spring until he saw the Allmans “peakin’ at the Beacon”). But they also accomplished it with a lot of new Brothers. Future co-founders of Gov’t Mule, Warren Haynes and Allen Woody, came in on guitar and bass respectively, but once Woody too died unexpectedly he was replaced by the incomparable Oteil Burbridge. And after Betts finally wore out his welcome for good – he was first suspended and ultimately ordered out of the band by Gregg for his excessive drug and alcohol use (you’d have to have been really messed up to have Gregg Allman tell you you’re too messed up) – a new prodigy arrived, who somehow seemed preordained. Derek Trucks, the baby-faced nephew of Butch Trucks, joined at just age 20, more or less stepping into the “Duane” role in the band. And while no one could replace Duane, it felt like Derek was put onto the earth to play the guitar in a manner strikingly like that of his forebearer. He was nothing short of a phenom: effortless, stunning, and sublime, and before long, the highlight of the live shows. Now, I’m often not much for bands with largely turned-over rosters, who at times can seem in the extreme like a cover band version of themselves. But with the post-1989 Allman Brothers, and especially starting in 1999 with the arrival of Derek Trucks, it wasn’t so much about replacements as it was a complete rebirth.

I began attending Allman Brothers shows at The Beacon regularly; another set of brothers, my friends the Barrs, had an “in” with the band (their cousin Johnny) who could always procure us good seats, and we made our own annual rite of at least a couple concerts a year. I also began taking my son to shows, perhaps way earlier than I should have, but unable to resist the awe of having him see history on stage each spring. One of the beautiful things about what became the 25-year Allmans @ Beacon run is that they really leaned into that history, constantly bringing in a vast array of influential and oft-forgotten artists to join them on stage for large segments of shows – players such as Little Milton, Taj Mahal, and Hubert Sumlin – while also inviting younger up-and-comers like Robert Randolph, Luther Dickinson, and Tash Neal, always in a communal-feeling effort to expose and support artists both past and present with like-minded fans. In 2009, to commemorate the band’s 40th anniversary, they even welcomed a guest appearance by a man receiving absolutely no introduction, Eric Clapton, who proceeded to play songs and trade guitar parts with Derek Trucks that he’d originally recorded in 1970 with Duane Allman as part of the quintessential Derek and the Dominos album Layla and Other Assorted Love Songs. Then, amidst a written invocation on a large screen above the stage reading “To the man who started it all,” came a succession of photographs of Duane, as Clapton and Trucks performed his guitar ballad ‘Little Martha’ before eventually closing the show with none other than ‘Layla.’ Yup, I was there, and it was quite a thing to behold.

Which brings us to 2014, when the band had resolved that they would finally be hanging up their instruments and retiring, and announced their final Beacon run, this time in the fall. Warren was going to devote more time to his work with The Mule, and at times to The Dead; Derek was ready to push his own juggernaut project formed with his wife, The Tedeschi Trucks Band, to another level; and Gregg and the other two surviving original members, Butch and Jaimoe, came around to agree that 45 years was a nice enough round number on which to call it a career. Demand for the shows was white hot. I got tickets to two. On a Friday evening I attended their 4th-to-last one with G. Barr and two other friends, Randy and Peter: It was a tremendous show, and we tied one on pretty good. The weekend, as a result, went by in a blur; Monday and Tuesday were particularly long slogs at the office; and by late Tuesday I was just not feeling it. Feeling what? I had tickets for the grand finale concert that night. I’m literally ashamed to admit this now, but I told my wife I was too tired, I was going to dump the tickets, and head home. To her everlasting credit, she quickly told me I was doing absolutely no such thing, called me a couple unmanly names, and said she was on her way into the city, where I should meet her at The Dublin House for a pre-show Guinness. Which, thank goodness, I did.

What can I say about that show (for which this one time there were no special guests), that epic culmination of 45 years for arguably the greatest American band ever. In all the years of Allmans’ Beacon shows they always held to the same general format: First set, intermission, second set, end about 12:00. On this night, 10/28/14, the band refused to let the clock strike midnight, finishing their second set (with the classic ‘In Memory of Elizabeth Reed’), before Gregg stepped back to the mic and said, “We’ll be right back,” with those four words electrifying the room and bringing continued glee to the 2,894 person capacity crowd (though probably more were actually jammed in). Eventually, after more than four hours of music, and the inevitable encore of ‘Whipping Post,’ the seven members of the group lined up onstage and took a bow, the only such occurrence in my memory. Then Gregg, seemingly pressed forward by the others, gave a brief speech, another first, in which he recalled the precise date, March 26th, 1969, that the original band first got together for a jam session in Jacksonville. “Never did I have any idea it could come to this,” he uttered almost sheepishly, as he gazed out to the adoring audience still standing and cheering at nearly 1:30 a.m. “Now,” Gregg finally added, “We’re gonna do the first song we ever played.” And with that The Allmans launched into ‘Trouble No More,’ the rumbling Muddy Waters tune from the opening side of their 1969 debut album. Moments before the song’s close, after the drummers marched to a stop (at 3:02 in the attached Fillmore recording), Gregg Allman let out one last raspy holler of “Goodbye, baby!” As Fricke later wrote of their final ferocious rendition, “It sounded nothing like goodbye. But it was.”

Leave a Comment