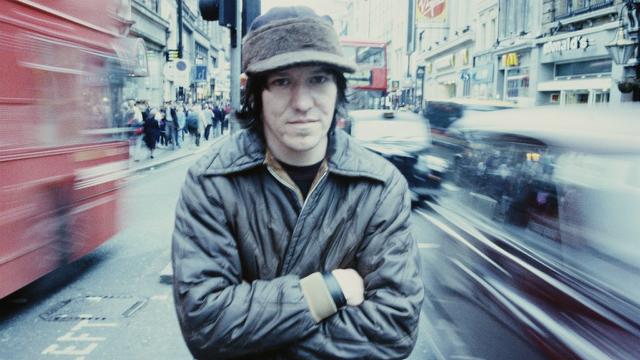

Matt Damon and Ben Affleck brought Elliott Smith to much of the world, but my son Max brought him to me. And I feel extremely fortunate that he did; Smith’s songs regularly reached a level of poignancy I think few artists achieve, or probably even seek. His sweet, breathy vocals, painfully personal lyrics, and stripped-down, mostly acoustic arrangements were pretty atypical for my usual tastes, but I quickly learned to appreciate him for the genius artist that he was. A hopelessly tortured genius artist, unfortunately, as it (seemingly) turned out.

This stark, beautiful song played over the closing credits of Damon and Affleck’s groundbreaking debut film, Good Will Hunting, and was so utterly perfect for the moment; it’s like it couldn’t possibly have been anything else. In retrospect, it seems as memorable a scene as any part of the actual movie.

In recognition of the date, YAHOO! today ran the following story.

*Re-printed from YAHOO!*

A fond farewell: Remembering Elliott Smith, 15 years after his tragic and mysterious death

The year was 1998. The 70th Academy Awards took place at the Shrine Auditorium in Los Angeles, and as Madonna approached the podium to present the Oscar for Best Original Song, it seemed a given that Celine Dion’s Titanic megahit, “My Heart Will Go On,” would take the prize. And of course, it did. But another, very un-Celine-like artist made a major impression that evening, performing his own nominated underdog ballad, “Miss Misery.”

His name was Elliott Smith. He was already a critics’ darling, and after this exposure, he was heralded as the next big thing. But just five and a half years after his breakthrough Oscars moment, this genius, one of the greatest singer-songwriters of the past 30 years, was dead. He was only 34.

Fifteen years ago, on Oct. 21, 2003, Smith died from two stab wounds to the chest. While his death was originally considered a suicide (eerily, another one of his songs, “Needle in the Hay,” had recently been the soundtrack for a suicide attempt scene in Wes Anderson’s The Royal Tenenbaums), the official autopsy report was inconclusive, opening up the possibility of homicide. Mystery and speculation surrounding Smith’s death persist to this day, and the Los Angeles Police Department’s investigation remains open. “The trauma that he sustained could have been inflicted by him or by another, and the coroner has not been able to make a determination,” a spokesman for the coroner, David Campbell, said in December 2003.

Smith had always been startlingly frank about his struggles with depression, addiction, and suicidal thoughts — long before such topics were commonly discussed by celebrities — in both his interviews and his lyrics. “I can’t prepare for death any more than I already have,” he once heartbreakingly warbled in the posthumously released “King’s Crossing,” for instance. The Independent even proclaimed Smith “up there with the likes of Sylvia Plath, Emily Dickinson, and William Burroughs” and “one of the greatest modern chroniclers of depression and addiction,” adding: “As a fictional memoir of a crippling addiction, Elliott Smith trumps Edward St Aubyn. As a portrait of personal despair, [fourth album] XO rivals The Bell Jar.” This, of course, made it rather easy to believe that this quintessential “tortured artist” could have died by his own hand. But many fans refused, and still refuse, to accept it.

The details of Smith’s case were investigated in William Todd Schultz’s 2013 biography, Torment Saint: The Life of Elliott Smith, which included conversations with Smith’s live-in girlfriend, musician Jennifer Chiba, who was with Smith when he died. In 2003, Chiba told police that she and Smith had had an argument, that he had stabbed himself after she locked herself in the bathroom, and that after discovering him, she had pulled the knife out of his chest before calling 911. Smith was pronounced dead 20 minutes after being taken to the hospital. A note in the couple’s Los Angeles apartment, written on a Post-It, read: “I’m so sorry — love, Elliott. God forgive me.”

It didn’t take long for conspiracy theories to circulate — implicating Chiba in the same vicious way that some Nirvana fanatics still steadfastly believe that Courtney Love killed Kurt Cobain. “I think part of it is misogyny. Hating on the evil harpy who supposedly destroyed the hero,” Schultz told the Independent at the time of his book’s release. Such speculation began, as Torment Saint notes, when the coroner’s report returned an open verdict, mentioning a lack of “hesitation wounds” and stating, “The location and direction of the stab wounds are consistent with self-infliction, [but] several aspects of the circumstances are atypical of suicide and raise the possibility of homicide.” It was also notable that Elliott’s first name was initially reported as being misspelled on the suicide note — as “Elliot,” with one t — although it later turned out that the misspelling appeared only in the coroner’s report of the note, not on the Post-It itself.

No one, including Chiba, was ever charged with Smith’s murder. And Schultz, who also extensively interviewed the coroner for Torment Saint, insisted to the Independent: “I’m convinced that he committed suicide. Everybody I interviewed for the book who would talk about that agreed, with maybe one exception — and that was someone who didn’t know Elliott all that well. We’re talking about a person who had overdosed numerous times in the last couple of years of his life, had cut himself, had always been depressed, was going through the difficult process of getting off the drugs that he was addicted to — and who was still feeling deeply paranoid because of all the crap he had used. He was suspicious of people spying on him, of trying to kill him. He was not in his right mind for the last two years of his life.”

Smith’s career had started out promisingly when he first came to underground fame as a co-founder of the Portland punk band Heatmiser in the early ’90s. He then grew his fan base with the solo lo-fi masterpieces Roman Candle (1994), Elliott Smith (1995), and Either/Or (1997), which helped usher in a new era of folk music (or anti-folk). But then he got what seemed like his big break when fellow Oregon indie icon Gus Van Sant enlisted him to contribute six songs to the Good Will Hunting soundtrack. This unusual partnership — which took place in an era long before hipster soundtracks (think Garden State, Twilight) became the norm, or before indie duo the Swell Season actually won a Best Song Oscar for their Once ballad “Falling Slowly” — was likened by critics to Simon & Garfunkel’s iconic music for The Graduate. Good Will Hunting introduced mainstream America to Smith’s brilliance, and when he appeared on the Oscars, it was by far the largest audience he’d ever faced.

Smith’s Oscar performance must have thrown many spectators, both at home and inside the Shrine Auditorium, for a loop. On a night dominated by Titanic‘s more-is-more aesthetic, when Dion performed with a full orchestra amid billowing dry-ice clouds, this unassuming, nervous guy in a rumpled suit seemed extremely out of place. Smith, who was shocked by the success of Good Will Hunting, reportedly didn’t even want to appear on the telecast. (“Most of those songs were recorded in a friend’s warehouse space on eight-track. I didn’t have any idea that they would be playing in a big movie theater. I didn’t have any idea that Matt Damon and Minnie Driver would be making out with one of my songs in the background,” he once told Billboard.) Smith only agreed to perform on the Oscars after producers informed him that if he didn’t, they’d book another artist to sing “Miss Misery” instead.

Speaking of the surreal experience, Smith later told Under the Radar that Dion “..was really sweet, which has made it impossible for me to dislike Celine Dion anymore. Even though I can’t stand the music that she makes — with all due respect, I don’t like it much at all — but she herself was very, very nice. She asked me if I was nervous, and I said, ‘Yeah,’ and she was like, ‘That’s good, because you get your adrenaline going, and it’ll make your song better. It’s a beautiful song.’ Then she gave me a big hug.”

It seemed Smith was uncomfortable with his elevated post-Oscars profile (“I went from being an anomalistic indie person to ‘Oscar Guy.’ And I didn’t really like it,” he told the Phoenix New Times), but like it or not, his gorgeous, melancholy music was getting the mainstream attention it deserved. He signed to DreamWorks Records, and a few months after the Oscars he released his fourth studio album, XO. The album traded his acoustic vibe for more lavish orchestration — thus diminishing the intimacy and pathos of his earlier unguarded work — but it was still one of the most critically acclaimed albums of 1998.

However, it turned out that Smith’s Oscars moment would be his commercial career peak. XO only sold about 360,000 copies. Smith’s DreamWorks follow-up, Figure 8, released in 2000, sold roughly 265,000. The three and half years between Figure 8 and Smith’s death were tragic and troubled, marred by aborted recording sessions, unsuccessful rehab attempts, shambolic concert performances, and his participation in a brawl at a Flaming Lips/Beck concert that led to his arrest. Smith even reportedly began to display signs of paranoia, telling his friends that DreamWorks was out to get him. His devoted fans waited patiently, hoping he would eventually return to making magical, heart-on-flannel-sleeve music. But Figure 8 would be the last album that Smith would release in his lifetime.

Smith never won the awards — Academy or otherwise — that he deserved while he was alive. But he remains a much-worshipped and important figure in indie rock to this day. Almost exactly a year after his passing, on Oct. 19, 2004, a posthumous compilation of unfinished tracks, From a Basement on the Hill, became his only Billboard top 20 album, charting at No. 19. His life and tragic death have been the subject of both Torment Saint and the 2015 documentary Heaven Adores You. And his music has inspired at least four tribute albums and has been elsewhere covered by the likes of Pearl Jam, Ben Folds, Jack Black, Third Eye Blind, Brad Mehldau, Rhett Miller, Beth Orton, Pete Yorn, and a very famous woman who shared the stage with him on Oscar night, Madonna.

Younger artists have also continued to discover Smith’s discography over the past 15 years. His influence can be heard in the quiet, mournful music of acts like Sufjan Stevens (who received an Oscar nomination of his own this year), Band of Horses, Iron & Wine, the National, Bon Iver, Frank Ocean (who sampled Smith’s “A Fond Farewell” on his Blonde track “Seigfried”), and countless emo bands.

When Larry Crane — Smith’s friend, co-producer, and the man appointed by Smith’s family to oversee his archive — spoke to Yahoo Entertainment in 2017 about the deluxe reissue of Either/Or (the album widely considered to be Smith’s best), he reflected on the dark, dramatic turn Smith’s career took after the Oscars exposure. “Good Will Hunting certainly changed everything,” he said. “I love Gus [Van Sant], he’s a great guy, but I kind of wonder, even if the songs were on the soundtrack, but that damn Oscar nomination… You look back and think, if that nomination hadn’t happened, [Smith] wouldn’t have gotten that whole rush of attention, and it might have been just a nice slower growth, and his whole life would have been different. But, you have no control over these things.”

RIP, Elliott Smith.

Article Comments