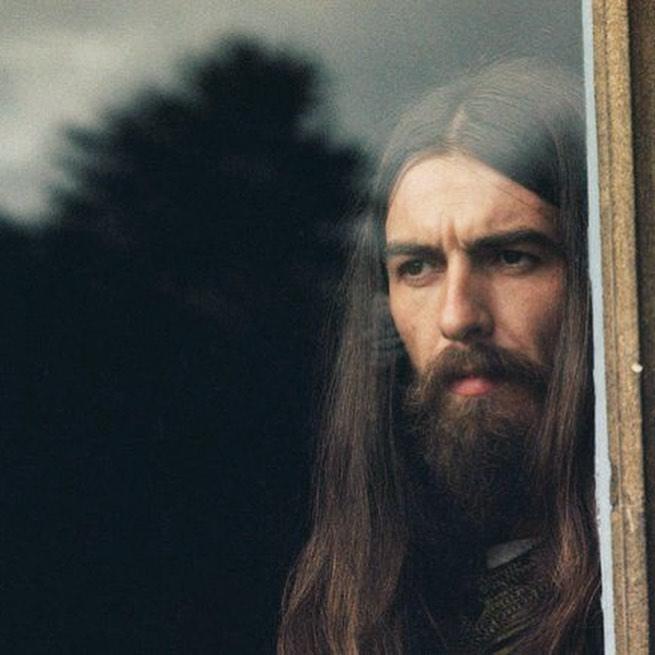

“The biggest break in my career was getting into the Beatles. The second biggest break was getting out of them.” — George Harrison

All Things Must Pass, the audacious masterpiece released 51 years¹ ago today, November 27th, 1970, was the greatest post-Beatles solo record of any of the former Fab Four. And as far as I’m concerned, it’s not even close. It was a creative emancipation for the Beatles’ supposed junior partner, George Harrison, who’d had the most extraordinary songwriting pair in popular music history, John Lennon and Paul McCartney, effectively standing on the garden hose of his artistry throughout most of Beatlemania and beyond. Harrison met the denouement of his former band with a veritable deluge; a triple-album, epic not simply for its unheard-of length but equally so for the massive “widescreen sound” engineered by George and his fabled co-producer, Phil Spector. And yet in remarkable contrast, Harrison, mere months removed from the “official” break-up of the Beatles (a slow-motion process that ebbed and flowed over the better part of three years), landed on a track and ultimately an album title that, according to Beatles musicologist Ian Inglis, worked incisively on two levels: a recognition of both the impermanence of human existence, and of the simple and poignant conclusion to Harrison’s world-altering prior band.

Of course, it’s not as if George, whose unassuming persona had forever labeled him “the quiet Beatle,” hadn’t already contributed some of the most conspicuous and historic pop gems filling the Beatles’ obviously unparalleled catalogue² (George’s song ‘Something,’ for instance, was called by Frank Sinatra “the greatest love song ever written”). But whereas Harrison had typically been allotted just two songs per Beatles disc, All Things Must Pass was his first genuine opportunity to function without restrictions. Aside from the seventeen compositions issued on discs one and two of the original album,³ Harrison actually recorded at least twenty other songs. In a 1992 interview, Harrison commented on the volume of material, saying “I didn’t have many tunes on Beatles records, so doing this album was like going to the bathroom and letting it all out.”

“Sunrise doesn’t last all morning / A cloudburst doesn’t last all day”

What poured forth was an extravaganza of musical brilliance, per a description in Rolling Stone “whose sheer magnitude and ambition may dub it the War and Peace of rock ‘n’ roll.”

- ‘My Sweet Lord’ – The Hindu-inspired incantation was the biggest selling single of 1971, the first #1 record by an ex-Beatle, and heralded the arrival of Harrison’s slide guitar technique, which one biographer described as “musically as distinctive a signature as the mark of Zorro.”

- ‘Isn’t It a Pity’ – An emotional as well as musical centerpiece of the album, it served as a disarming reflection on the Beatles’ turbulent ending. UK journalist Kitty Empire said it “functioned as a kind of repository of grief” for the band’s distraught fans.

- ‘What Is Life’ – The catchiest pop, even Motown-spiced, tune on the album, it’s one of several Harrison love songs that appear to be directed at both a woman and a deity. The track opens with George playing an irresistible descending fuzztone guitar riff, and proceeds from there as an exultant, uptempo declaration of joy.

- ‘Wah-Wah’ – The first song recorded for the album, and also the first ever performed live by George as a solo artist (at his Concert for Bangladesh), Harrison wrote it following his temporary departure from the Beatles in early ’69 as an expression of his frustration with the crippling atmosphere then surrounding the group. You’d never know it, however, from the magnificent musicality, which Rolling Stone aptly described as “a grand cacophony of sound.”

- ‘Beware Of Darkness’ – Curiously complex harmonic progressions mix with Krishna-inspired admonitions warning against allowing material illusions to supersede one’s true spiritual purpose to produce a meditative and enchantingly beautiful ballad that must rate among the finest compositions of Harrison’s entire career. The dramatic yearnings and melodic intricacies – which have been compared to both Brian Wilson and impressionist French composer Claude Debussy – were casually presented by Harrison to co-producer Spector as sessions for All Things Must Pass were getting underway in May, 1970. “Here’s the last one I wrote,” said George, “just the other day.”

- ‘I’d Have You Anytime’ – Two years prior to All Things Must Pass this gentle ballad and album-opening track was co-written with Bob Dylan at Dylan’s home near Woodstock, NY. It’s recognized as a statement of connection and friendship between the two generally reclusive personalities, whose meetings beginning in 1964 brought about change in musical direction for both Dylan and the Beatles, and presaged the formation of the Traveling Wilburys in the late ‘80’s.

- ‘Awaiting On You All’ – The most overtly religious composition present, Harrison projects his espousal of a direct relationship with God over adherence to the tenets of organized religion. He sings “By chanting the names of the Lord and you’ll be free / The Lord is awaiting on you all to awaken and see,” yet still manages to deliver his message in a rocking, gospel-fueled, reverb-heavy celebration.

- ‘All Things Must Pass’ – Harrison actually introduced the anthemic, titular song at the Beatles’ Let It Be rehearsals, only to have it rejected by Lennon and McCartney. Instead it became a representation of a singular moment in pop culture history, the symbolic requiem to the greatest rock and roll band ever.

That abundance of luminous output is not even half of the songs on the main body of the album. An amazing “Wall of Sound” expanding across a colossal mountain of tunes. In sum, I think it’s no exaggeration to state that it was Harrison, decidedly more than the legendary Lennon and McCartney, who forged the most weighty post-Beatles solo career, even if considered almost entirely for this one awe-inspiring collection.

“It’s not always going to be this grey”

All Things Must Pass was nominated for Album of the Year at the 1972 Grammys (where it lost out to another arguably “perfect” album, Carole King’s Tapestry). Nonetheless, it was an enormous commercial success, certified six times platinum by the Recording Industry Association of America – which, for a bit of context, represents sales of more than Lennon’s Imagine and McCartney (and Wings’) Band on the Run combined!

Still, it was the universal acclaim generated by the now mythologized Harrison breakthrough that seems most relevant, especially looking back half a century later. For certain critics, attention was focused on “a major talent unleashed, one who’d been hidden in plain sight all those years.” Others seemed almost stupefied that “the quiet Beatle” was even capable of something so monumental, finding George’s underutilized true capacities “revelatory.”

Perhaps, though, the key to understanding All Things Must Pass is in what might have been. What might the Beatles have sounded like in their unprecedented decade between 1960 and 1970 had George’s potential been nurtured rather than mostly squelched? George Martin, their producer, arranger and ostensible “fifth Beatle,” once offered a keen observation. “George’s songwriting was always painful for him because he had no one to collaborate with, and John and Paul were such a collaborative duo. They might throw out a word of advice to him and so on, but they didn’t really work with him.” In the band’s later stages, Paul had a growing tendency to be dictatorial over George’s contributions, while John became increasingly dismayed and jealous of George, even at his stifled level of productivity. Could a songwriting team that more equitably included George’s demonstrably dazzling aptitude have conceivably given rise to a different Beatles? And, most intriguingly, might such a three equal-creative-parts Beatles (no intended disrespect to Ringo, but his lyrical and composing skills simply could not be considered in the same league) have possibly survived the dismal, mostly self-imposed turmoil that marked their late ‘60’s demise, instead allowing themselves the opportunity to evolve and flourish into another manifestation of history’s greatest band into the 1970’s and beyond.

“Daylight is good / At arriving at the right time”

Amongst these and other such unanswerable questions, the liberated George, for one, did not seem a trifle bothered. The triumphant triple-album had elevated ‘the third Beatle’ into a position that, at least for a time, comfortably eclipsed that of his former bandmates. In a PopMatters review, All Things Must Pass was likened to “The sound of Harrison exhaling. He was quite possibly the only Beatle who was completely satisfied with the Beatles being done.” In 2000, just one year before his death at the age of 58, George himself reflected on the work that resulted in his milestone record. “It’s just something that was like my continuation from the Beatles, really. It was sort of getting out of the Beatles and just going my own way. It was a very happy occasion.”

“All things must pass / All things must pass away”

Five decades and a year on, All Things Must Pass remains a timeless marvel, a paragon of post-Beatles excellence, that also helped to define the ‘70’s decade it ushered in (which would happen to become the best single decade popular music has ever seen). Being in the greatest band of all time implausibly held George back. It’s terribly unfortunate that the Beatles broke up and never reunited. But then, logically, we would have never gotten All Things Must Pass. With the benefit of hindsight, maybe it was worth it.

¹I know, a 50-year anniversary recognition would’ve been patently more appropriate, but I couldn’t get it together last year

²All the songs George Harrison wrote for the Beatles:

-

- ‘Don’t Bother Me’ – With The Beatles

- ‘I Need You’ – Help!

- ‘You Like Me Too Much’ – Help!

- ‘Think For Yourself’ – Rubber Soul

- ‘If I needed Someone’ – Rubber Soul

- ‘Taxman’ – Revolver

- ‘Love You To’ – Revolver

- ‘I Want To Tell You’ – Revolver

- ‘Within You Without You’ – Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Heart’s Club

- ‘Blue Jay Way’ – Magical Mystery Tour

- ‘While My Guitar Gently Weeps’ – The White Album

- ‘Piggies’ – The White Album

- ‘Long, Long, Long’ – The White Album

- ‘Savoy Truffle’ – The White Album

- ‘It’s All Too Much’ – Yellow Submarine

- ‘Only A Northern Song’ – Yellow Submarine

- ‘Something’ – Abbey Road

- ‘Here Comes The Sun’ – Abbey Road

- ‘I, Me, Mine’ – Let it Be

- ‘Dig It’ – Let it Be

- ‘For You Blue’ – Let it Be

³disc three, also known as Apple Jam, was a series of instrumental jams, less consequential in terms of memorable songs however directly responsible for the formation of a subsequent band among four contributing players to All Things Must Pass: Bobby Whitlock, Carl Radle, Jim Gordon, and Eric Clapton, who together declared themselves Derek and the Dominos while participating in the sessions.

Rob MacMahon

November 27, 2021 4:23 pmBG: My fave Beatle, hands down. And this article is beautifully written. I hv loved this album since my oldest sister brought it home. Hope your holiday wknd has been happy. R