There’s never been a band with a more innocent, clean-cut image than the Beach Boys. Their forever portrait of five cherubic chums collectively holding a surf board in matching outfits on the beach is as much an iconographic symbol of wholesome Americana as baseball, hot dogs, apple pie and Chevrolet. But the divergent reality was this: none of the Beach Boys actually surfed, let alone even really digged the ocean, except for one, drummer and middle Wilson brother, Dennis. And that same Dennis Wilson, for a significant length of time, hung out with one of the most notorious embodiments of evil of the 20th century, Charles Manson.

Few in the Beach Boys orbit actually lived the unblemished existence created and then cultivated through the band’s collective identity: Brian Wilson was driven mad by his own genius and suffered a nervous breakdown; Mike Love was endlessly envious, spitefully litigious, and turned out to be a colossal asshole in almost every imaginable regard; and to varying degrees all band members were habitually tormented, even tortured, by the band’s tyrannical and impossible-to-please manager, the Wilson brothers’ own father, Murry.

Still, Dennis was different. He was the wild one, the cool one, and not simply because he was the lone surfer whose personal life most closely exemplified the “California myth” celebrated in the band’s earliest songs and persisting imagery. Dennis was ever rebellious, the self-proclaimed black sheep of the family who’d been nicknamed “Dennis the Menace” as a child. And while Murry manipulated the band’s beachy and peachy representation to the point of caricature, seemingly stuck in the virginal ‘50’s, Dennis always maintained an edginess, a desirably dark mystique, like George in The Beatles, that somehow distanced him from their stodgy “endless summer” vibe while bridging the discontented sensibilities of the tumultuous ‘60’s environment in which the Beach Boys actually existed.

By the late 1960’s the Beach Boys popularity was at its lowest ebb, their cultural standing especially worsened by their inapt public image which remained incongruous with their peers’ “heavier” music. Dennis, in particular, descended into derelict drug use and progressively dangerous behavior. On April 6, 1968 Wilson picked up two female hitchhikers, one of whom was Patricia Krenwinkel. Five days later he picked the same pair up again, this time bringing them to his home on Sunset Boulevard, where Dennis discussed his recent involvement with transcendental meditation and The Maharishi, and Krenwinkel offered that they too had a guru, a guy named Charlie. Upon returning from a recording session later that night, Wilson was met in his driveway by Charles Manson, while also finding over a dozen members of the “Manson Family” occupying his house. Wilson befriended Manson, housing much of the “Family” for nearly six months. Responding to reporters at the time who asked if he had been supporting them, Wilson replied, “No, if anything they’re supporting me. I had all the rich status symbols – Rolls Royce, Ferrari, home after home. Then I woke up and gave away 50 to 60 percent of my money. Now I live in one small room, with one candle, and I’m happy, finding myself.”

Dennis even subsidized Manson’s alleged singer/songwriter aspirations, arranging recording sessions for Manson at Brian Wilson’s home studio. One of the songs they produced, a Manson composition entitled ‘Cease to Exist,’ was later reworked by the Beach Boys and released under the name ‘Never Learn Not to Love.’ The writing, however, was attributed solely to Dennis Wilson. Asked why Manson was not credited, Wilson explained that Manson relinquished his publishing rights in favor of “about a hundred thousand dollars worth of stuff.” In due course, Wilson grew fearful of the increasingly bizarre situation and ultimately distanced himself from Manson, even moving out of his own house where virtually all of Wilson’s household possessions would be stolen by the “Family” before eventually being forcibly evicted. Manson continued to seek further contact, initiating a series of threats including once the delivery to Wilson of a single bullet. When Dennis asked, “What’s this?” Manson replied, “Every time you look at it, I want you to think how nice it is your kids are still safe.” A short time later the Manson Family perpetrated the infamous Tate-LaBianca murders. During Manson’s ensuing trial, prosecutor Vincent Bugliosi attempted to procure tapes of the songs that Manson had recorded with Wilson, but Wilson responded saying that he had destroyed them because “the vibrations connected with them didn’t belong on this earth.”

Some, including biographer Mark Dillon, attributed Wilson’s subsequent spiral of self-destructiveness, particularly his feverish drug intake, to the fears and overwhelming feelings of guilt for having ever introduced Manson, the sociopathic persona of evil, into the music and Hollywood scene, and recounted that he’d become “So freaked out he just didn’t want to live anymore.” Said Dillon, “He was afraid, and he thought he should have gone to the authorities, but he didn’t, and the rest of it happened.” In December of 1983, Wilson, by then living a nomadic, drug-addled, quasi-homeless life, followed up a day-long drinking binge by diving into the waters of Marina Del Rey purportedly attempting to recover his ex-wife’s belongings (which had previously been thrown overboard from his yacht three years earlier amidst their acrimonious divorce). In the ultimate irony, the one Beach Boy who actually lived with and loved the ocean, drowned to death. He was 39. One week later, per Dennis’ delineated wishes, the U.S. Coast Guard buried his body at sea, at the time the first non-Coast Guard or Navy veteran to be so accommodated, and made possible only through intervention by then-President Ronald Reagan. Wilson’s own song, ‘Farewell My Friend,’ was played at the ceremony.

But before the sea had twice claimed him, Dennis Wilson left behind more than simply his mighty contributions to one of the best and most beloved bands in American history. By 1977 Dennis had amassed a stockpile of songs he had written and partially recorded on his own as dissenting factions within the Beach Boys circle became too damaging and stressful for him, and he was signed to a contract with Caribou Records to bring to realization a solo project whose multiple prior attempts dated back as far as 1970. Label owner James William Guercio handed Wilson full control, directing him to “complete his vision, finish his dream. It’s your project; you’ve got to do what Brian used to do.” The result was the magnificent unpolished gem “Pacific Ocean Blue,” released in August of 1977. It sold relatively poorly (though still outperforming contemporaneous albums by the Beach Boys), but received warm, albeit limited, critical response.

In the years and decades since it has been substantially reevaluated by music chroniclers and journalists to become widely praised, even developing a status as a lost masterpiece, a quasi-cult item (Manson pun unintended), appearing in the musical reference book “1,001 Albums You Must Listen To Before You Die,” Mojo Magazine’s “Lost Albums You Must Own,” and GQ’s “The 100 Coolest Albums in the World.” The familiar stacked production is there, the recognizable Beach Boys “sound,” but Dennis’ raw, weathered vocals bring the listener to a discretely different place. Even amidst the Beach Boys’ pristine harmonies – arguably the greatest ever in popular music – Brian Wilson once said that the mix never sounded quite right without Dennis’ voice. Here, coming near the end of a life filled with whiskey, cigarettes and turmoil, Wilson’s delivery is grainy and rough, yet deeply and unmistakably soulful. Writer Peter Doggett later said that Dennis’ performance on the album “showed for the first time an awareness that his voice could be a blunt, emotional instrument, an erratic croon that cut straight to the heart, with an urgency that his more precise bandmates could never have matched.”

Back in 1964, just two years into the Beach Boys legendary reign but already on their sixth album, “All Summer Long,” the then-20-year-old Dennis Wilson fatalistically contributed the following passage to the album’s liner notes: “They say I live a fast life. Maybe I just like a fast life. I wouldn’t give it up for anything in the world. It won’t last forever, either. But the memories will.” Here’s to the hauntingly beautiful good vibrations that live on through Dennis Wilson’s long-delayed and late-appreciated solo opus “Pacific Ocean Blue,” and to those timeless surfin’ safari memories of the one true Beach Boy.

Rob MacMahon

June 29, 2021 12:50 pmExcellent write-up, again, BG. Very interesting back-story on this Wilson brother’s run-in with the Manson gang. Pretty scary, too. Ironic end to this only real “beach” boy’s colorful, yet drug-addled life. A shame, really. I tried getting into this album a while back and I just couldn’t embrace it. Found it somewhat dull.

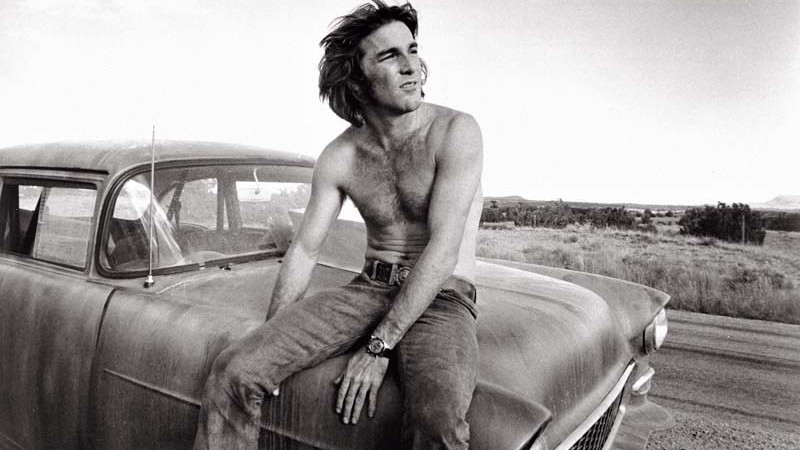

PS: Hunt down the very strange 1971 movie Two-Lane Blacktop with Dennis and James Taylor (from which that photo above is taken). Very weird 70s cinema.